- Italy Tours Home

- Italy Ethos

- Tours 2023

- Blog

- Contact Us

- Dolomites

- Top 10 Dolomites

- Veneto

- Dolomites Geology

- Dolomiti Bellunesi

- Cortina

- Cadore

- Belluno

- Cansiglio

- Carso

- Carnia

- Sauris

- Friuli

- Trentino

- Ethnographic Museums

- Monte Baldo

- South Tyrol

- Alta Pusteria

- Dobbiaco

- Emilia-Romagna

- Aosta Valley

- Cinque Terre

- Portofino

- Northern Apennines

- Southern Apennines

- Italian Botanical Gardens

- Padua Botanical Garden

- Orchids of Italy

The Plains Around Bologna: Unexpected Pockets of Interesting Nature in an Otherwise Flat Landscape.

The purpose of this page is to explore the plains around Bologna. There are several areas of natural beauty near the city – the regional capital of Emilia-Romagna – but the attention is generally drawn to the Apennines to the south; here, however, there is a specific dedication to the flat lands which extend to the north of Bologna (a typical image of the landscape of these plains is shown above).

The reason is that the plains around Bologna, quite unjustly, tend to be overlooked at the expense of the hills; therefore, I am intending to show that there are several motives of interest – for the nature lover – even in the flat expanses that open up to the north of the city. This area includes various nature reseves and museums related to nature or to the traditional way of life; one such institution is the “Museum of the Farming Civilization” (Museo della Civiltà Contadina) in San Marino di Bentivoglio, hosted in the noble setting of 17th Century Villa Smeraldi (second picture above).

The Museo della Civiltà Contadina in San Marino di Bentivoglio

The Villa, the Institution and the Museum

Villa Smeraldi is situated about 15 km from the centre of Bologna, along a stretch of the Canale Navile – a navigable canal that links the city to the small town of Bentivoglio and beyond to Ferrara. The Villa Smeraldi hosts the collections and the exhibitions of the Museo della Civiltà Contadina since 1973. In 1999 it gave its name to the institution – created jointly by the Province of Bologna and the municipalities of Bologna, Castel Maggiore and Bentivoglio – which runs the museum and the whole compound of buildings that host the collections.

The Park and its Historic Buildings

Built in different phases along the course of the 1800s and known under the name of its last proprietors, Villa Smeraldi shows – through the different buildings that compose it – its original double destination. The villa, the ex-horse stables, the ice-house, the larder and the vast park – landscaped in English style – all witness the way of living in the country houses of rich aristocratic or bourgeois families, mostly land owners, in the plains around Bologna at that time (a view of the villa and the park is presented below). While the farmer’s house – with its large kitchen, the tower-granary, the pigeon-house and the so-called tinazera (cellar) – refers to the historic function of this building as the centre of technical and economic organization in a large agricultural estate, composed of dozens of small farms, cultivated and run according to the ‘mezzadria’ (small farm) system.

The New Exhibition Spaces

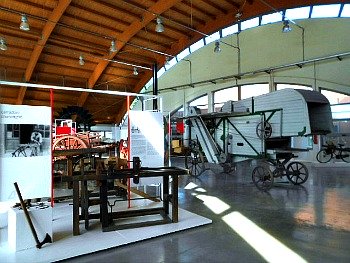

Planned and built since 1989 on the agricultural land next to the ancient park, the two new large pavilions that host the main collections of the museum’s permanent exhibitions are the most recent addition to the Museo della Civiltà Contadina, and now constitute its core. They are connected by a structure which is entirely built in glass that faces the old park; this part hosts the visitor centre and the bookshop, while a small relax area has been newly landscaped in the parterre just outside (below, an image of the interior of the new pavilions, composed of two wide open vaults covered by wooden beams).

A Visit to the Museum

The route of this important exhibition starts at the entrance of the new pavilions and is articulated in several sections, dedicated to different themes and aspects of life in the plains around Bologna. The introductory section shows the reasons behind the museum and introduces the experience of a visit, while reminding the names and the communities of residence of the families of farmers – the so-called ‘Gruppo della Stadura’ – that have allowed, thanks to their donations, to form the original core collections of the museum, which have now considerably grown.

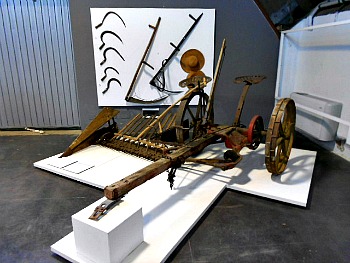

This museum is pivotal in order to reconstruct various aspects of life in the plains around Bologna in the old times, and it is instrumental – if you are not familiar with the area – to its educated visit. Following here are briefly described the different sections of the museum (in the picture below, an impressive piece of machinery related to the introduction of steam-engine in the countryside, which caused a considerable revolution in agricultural practices; this piece is hosted in the new wing of the museum).

The Plains of the ‘mezzadri’, the Fens (‘valli’) and the Rice-fields

A selection of documents (geographical maps, paintings, drawings and photographs) and some material evidence provides an overall idea of the evolution of this flat territory between the half of the 18th and the 19th Century, focusing in particular on the relationship between land owners and land workers, and the progressive formation – besides the ancient pole of the ‘mezzadria’ (tenant farmers), and the so-called ‘economy of bread and wine’ – of the other pole of rice cultivation and the ‘braccianti’ (literally, ‘arm-workers’), who played such an important part in the agriculture of the plains around Bologna.

The ‘podere’ (Small Farm)

The basic cultural unit of the plains around Bologna was the ‘podere’ (small farm), whose dimensions were in strict relationship with those of the families of the ‘mezzadri’ that lived in them, and the animal power they had available – as this was necessary in order to plough particularly hard lands and to transport and move manure and agricultural products inside and outside the farm. This section illustrates the constitutive elements of the ‘podere’: fields, meadows, pastures, the sequence of trees and vineyards, the hedges and ditches, while describing their different functions and evolution.

Wheat and Corn

The centrality of wheat and the role of corn in the farmer’s agriculture and also in rural and urban nutrition are documented through material evidence related to the phases of their cultivation cycle: from sowing to the struggle against weeds and diseases; from harvesting to threshing; from sorting the products of the land on the farmyard to the conservation of wheat in the farmers’ silos and in those of the land owners; from transportation to grinding in the mills; from the conservation of flour to use of its by-products – such as bran (an example of tools and machinery from this section of the collection is portrayed above).

Wood, Leaves and Wine

This section illustrates the plurality of functions carried out by the secular form of training trees and vineyards characteristic of the plains around Bologna and in Emilia-Romagna in general – the so-called ‘piantata’ – and aims to explain its evolution and near-disappearance. This section also highlights the importance of tree and vine leaves in the feeding of animals; the centrality of firewood for heating purposes and the cooking of food in the farms – but also in city homes (thus pointing to the constant relationship and exchange between countryside and the city – so near and yet felt as so distant by those who lived and worked here); also, it is stressed the importance of wood as raw material for the work of artisans. This section reconstructs the phases of cultivation of vineyards, and illustrates the old ‘cellar practices’ characteristic of the plains around Bologna too (a selection of tools and implements from this section is shown below).

The Farmhouse and its Courtyard

Farm courtyards were usually composed by a series of buildings that offered shelter to both men (home) and animals: the farm/barn and the hen-house/pigsty, plus the oven. In reference to the latter buildings, here are illustrated the practices of animal farming, from those related to work in the fields to the production of meat and milk; from pigs and poultry – raised for the production of meat and eggs for the family and the market – to the horse used for the pulling of vehicles destined to the transportation of people and the lightest weighs. As for the house, here are evoked dimensions, composition, hierarchy and the division of work within the families of ‘mezzadri’, and it is also reconstructed the only space (the bedroom) reserved to each single family unit (it is shown in the picture below). As for the well – source of water for men and animals alike – here are documented the equipment and the different phases of the traditional way of washing clothes.

Artisans and Farmers

The communities of the countryside have considered for centuries the presence of a variety of artisan activities as strictly interconnected with the life and work of the farmer’s families. Starting with the furniture, the tools and the products of the workshops of the artisans of wood (woodworkers, wain- and wheelwrights, barrel makers, broom makers) to iron (blacksmith, farriers, sharpeners) and the ambulant artisans (basket makers, chair makers, mattress makers, shoemakers, tailors, barbers, sawyers), this section aims at unfolding the theme of the relationship between different artisan activities, farmer’s agriculture and rural life in the plains around Bologna (in picture below, see an example from the production of the chair maker, with a milling wheel in the background).

Making Life Less Bitter: Sugar and Honey

Displayed in the ground floor of the former horse stable, the sub-section dedicated to honey – the most widely used sweetener for centuries – gathers the instruments typically used by a beekeeper in the plains around Bologna in the transition phase between farmer’s apiculture and the rational beekeeping of more recent times, linked to the use of modern beehives. A more spacious set-up on the same floor is dedicated to the cultivation of those plants from which sugar is obtained: sugar cane, with an indication of the worldwide distribution of its cultivation as well as information on sugar trading, and sugar beet, of which – through the material contained in the museum – are reconstructed the local practices of cultivation in the first half of the 20th Century, when its diffusion in this area after the experimentations of the 19th Century was significantly extended to the rest of the Po plains, thus enhancing the development of a dense network of sugar beet plants all over the Po valley (a poignant reconstruction of the hard work of sowing sugar beet – a labour intensive crop – is represented in the picture below).

A Versatile Fibre: Hemp

The plains around Bologna have been the classic centre for the cultivation of hemp in Italy for centuries: around half of the 1800s, more than two thirds of the raw product was being exported to other Italian provinces and abroad from here. The rest was the object – in Bologna and in the surrounding minor centres scattered in the countryside – of different processes such as rope making, filature and weaving, which occupied thousands of artisans, people working in their home and factory workers. This section of the museum documents all the main phases of cultivation and processing related to hemp: from sowing to collection through maceration, cleaning and separation of the fibres, and lastly combing, filature and weaving. The reconstruction of the different practices pertaining to each phase is represented by the tools employed, photographs, drawings and texts, and occupies the whole upper floor of the former stables building, atmospherically covered by old wooden beams (as portrayed in the image below).

Know Your Fruit by Eating it!

In the typical farmer’s agricultural practices and in the overall economy of the eastern provinces of Emilia-Romagna, the cultivation of fruit trees and the industry of fruit production take on a very important role in the first few decades of the 1900s. Set in the elegant interior of the old villa, with the supervision of the University of Bologna, this section aims to reconstruct this development and displays documents that pertain to the teaching of fruit tree cultivation techniques provided by that University – as well as evidence of the itinerant teaching posts of agriculture that traveled the countryside at that time. On demand, visitors can also book the participation in a workshop which involves the identification and tasting of different fruit species and varieties.

The Farmer’s Kitchen

On the ground floor of the old villa – in a room that once hosted the kitchen of the house – this space was rebuilt with the help of original pieces of furniture from a large farmer’s kitchen, with the wide fireplace, the corner where to dry hemp and the oven to cook bread. At the centre is the huge table around which the family members would sit; along the walls are the tools used to prepare bread, pasta and polenta and to process pork meat, or used for the consumption of water, for heating purposes and for the lighting of the house (an image of the old reconstructed kitchen is shown below).

Around the Museum: Bentivoglio

The area around the museum is interesting in its own right. In Bentivoglio itself there is a castle, which is of Medieval origin – despite having been remodeled at the beginning of the 20th Century, when there was a Medieval renaissance in the area (see a picture below). Having been used previously as a hospital, and partly still a private residence, the building cannot be visited, but it is still an atmospheric sight, right at the centre of town, which is also worth seeing for its former mills and the wharves’ area, now reconverted (the Canale Navile – once an important waterway between Bologna and Ferrara – still crosses the village).

This also means that the area was once very rich in water. There is still an abundance of it, in fact, with many canals crossing the countryside, but its use is far less than it used to be (it is a shame that the Canale Navile is not equipped for barges, as it would provide a terrific way of connecting two important cities by boat, with interesting sights on the surrounding plains and some of the towns en route – just like Bentivoglio).

A remnant of traditional activities connected with water, however, can still be enjoyed in the rice-fields east of Bentivoglio (pictured below): even though the extension of this area is quite small, it does provide an interesting insight on the past and on traditional activities that have almost completely disappeared from this part of the Po valley – and certainly from the plains around Bologna.

The Countryside Around Budrio

The area surrounding the town of Budrio (interesting in its own right for its small historic centre) presents several motives of interest – especially in the area around the hamlet of Bagnarola, where there is an interesting sequence of old villas, and Mezzolara, where there is a small wetland area (which is shown in the picture below).

In Bagnarola, also, a route has been devised to help one become acknowledged with some of the features of the old methods of land use and traditional agriculture – some of which are luckily making a comeback. Amongst these features are the hedge and the ancient piantata padana; that is, the ancient custom of combining vines and trees as a support.

The hedge is a dense strip of vegetation, wide and rich in small trees and shrubs that twist and turn in an irregular but linear fashion for some distance, with the goal of delimiting areas and creating boundaries. The vegetation that composes it develops at different height levels, from low to higher shrubs, up until the canopy of trees.

But what is its use? Widely spread in the plains around Bologna and in the territory of the Po plains at large until not long ago, a hedge responded to several precise needs related to agricultural works – specifically, delimitation and enclosure of fields and of the estates or farmsteads, giving also important raw materials and produce such as fruits, berries, fresh leaves and timber. The intensive cultivation and the massive mechanization of agricultural practices in the last few decades has determined a drastic reduction in the number of hedges and trees in the Po valley, provoking the death of a great number of animals that lived in them, and causing in turn a progressive impoverishment and deterioration of the habitats and biodiversity in general.

Specific studies have by now demonstrated that the hedges and rows of trees carry out important functions for the environmental balance – such as enhancing biodiversity, climate regulation and restoration of ideal conditions for the presence of a varied fauna. Luckily, since the 1990s, European Directives and International Conventions have started to protect their ecological function, as well as promoting their naturalistic and landscape value.

But who lives in a hedge? The belief that hedges and uncultivated areas be breeding grounds of poisonous insects that are damaging for the agriculture has been fortunately overcome, unmasking its falsity; on the contrary, it was discovered that right there find nourishment and shelter the natural antagonists – vertebrates and invertebrates – of precisely those phyto-pathogenic and other agents that attack crops. A ‘good’ hedge can host 10 to 20 species of birds and as many mammal, reptile and amphibian species – besides insects in their hundreds (below, a hedge in Budrio in its winter outlook).

History of the Land: the Centuriation

The first Roman settlements in the area date to 189 a.C. The Roman centuriation (i.e. the organization of the land by dividing it into regular parcels of arable land) subdivided the territory by means of a network of parallel and perpendicular roads (‘centurie’), distanced 2,400 feet (which correspond to 710,4 metres), further subdivided into squares (‘actus’) of 120 feet for each side; two ‘actus’ corresponded to a jugerum – the surface that can be ploughed by two oxen in a day’s work. Remnants of this ancient land arrangement are still clearly detectable today in the network of perpendicular roads across this flat countryside, which can especially be appreciated with an aerial view.

As for the historic villas which can be admired in the vicinity of Budrio (mostly at Bagnarola), here is a selection of the most noteworthy ones:

Palazzo Bentivoglio-Odorici

Also known as “Palazzo di Sopra”, square and massive, on a rectangular base with protruding angles so to appear turreted, this building was founded in the 1500s and belonged to the Bentivoglio family until the 1700s, when it was purchased by the treasurer Antonio Odorici, who made it magnificent by adorning its immense rooms and halls, the gallery and the chapel with stuccoes, statues and tempera paintings – largely the work of Nicola Bortuzzi.

Palazzo Ranuzzi-Cospi

Also known as “Palazzo di Sotto”, it already existed in the 1500 in the form of a villa. In the 1770s the Count Ranuzzi-Cospi transformed it at the hands of architect Bertelli, who enriched it to the north with a magnificent three-arcaded loggia. To the sides, this magnificent scenography is enclosed by two symmetrical buildings with identical façades, both resembling religious buildings but that present differing structures at the back, linked to their specific function: one is really a chapel, while the other is a ice-house (a panoramic view of the main villa with the two side buildings is shown above). During the 1700s, one of these dependances was also the headquarters of a Literary Academy, “I Notturni” (‘the Nocturnes’), which transformed the villa in a centre of culture for the high society (see a winter image of the chapel below).

Villa Malvezzi-Campeggi

The most important villa in Budrio, however, is Villa Malvezzi-Campeggi, composed of two buildings – the so-called Aurelio and Floriano. A winter image with the entrance gate of the villa is shown below. The buildings are rich in paintings, frescoes and old pieces of furniture; unfortunately, however, the villa is privately owned and therefore it is not possible to visit it, if not on special occasions, but its vast garden is an important oasis for the local fauna – especially birds; in fact, the whole system of villas around Bagnarola ends up being an important ecological corridor in the middle of the plains around Bologna, which are certainly not an area rich in wooded areas – so that here every single tree counts.

The Castle of San Martino in Soverzano

Other fascinating pockets of territory are scattered in the plains around Bologna. Going east to west, from Budrio towards the town of San Giovanni in Persiceto, one encounters for instance the turreted castle of San Martino in Soverzano (pictured below). The structure is originally Medieval, but the compound has been heavily remodeled with mock additions during the latter part of the 19th Century. Even so – and although the castle itself cannot be visited inside – it still provides a pleasant sight, surrounded as it is by a moat, a lush garden and a small hamlet with an old arcaded building (dated 1684), where ancient country fairs used to be held (this still happens today during the summer months).

The System of Protected Areas Around San Giovanni in Persiceto

In the area surrounding San Giovanni in Persiceto – a medium-sized town to the north-west in the plains around Bologna – is an interesting system composed of various small protected areas and a few notable museums that support them.

Just outside San Giovanni in Persiceto itself, the Bora Nature Reserve is a S.I.C./Z.P.S. (Special Protected Area at EU level) of about 40 hectares, of which 22 are characterized by a wide former water reservoir, a small hygrophilous wood, hedges and wood thickets, plus a vast area organized as a meadow, as well as a new plantation with more than 8,000 trees (the picture below shows one of the small wetland areas that have been delimited inside the reserve).

The Bora was created in an ex-clay pit, which originally was abandoned and then recuperated thanks to a project which was carried out jointly by local environmental associations and the municipality. The central area of wetland of about 7 ha constitutes a water environment very rich in species, mostly birds. The hedges, the meadow and the new plantation – which by now has effectively become a patch of woodland – also offer original and precious habitats.

By the entrance of the protected area is the “Centro Anfibi e Rettili della Pianura”, where research and conservation activities are being carried out as regards to the amphibian and reptile population present in the area; the ponds in the reserve are also the object of research activities, as well as used for propagation and diffusion of the local hygrophilous flora, belonging to either rare or little widespread species. The protected area is endowed with a small Visitor Centre with a lecture room, where are also exhibited several zoological collections, of which one dates back to the 1800s; there is a small Naturalistic Collection too (below, an atmospheric image of the main wetland area at the Bora with the central pond – often shrouded by thick mists during the winter months).

In the centre of San Giovanni in Persiceto there is also a small Botanic Garden dedicated to Ulisse Aldrovandi (one of the founders of the historic Botanical Garden in the centre of Bologna). In this pleasant setting are hosted more than 300 plant species, in the context of the “Museo del Cielo e della Terra” (Museum of the Earth and of the Sky; below, see a picture of the garden’s Arboretum in winter).

Return from plains around Bologna to Emilia-Romagna

Return from plains around Bologna to Italy-Tours-in-Nature

Copyright © 2013 Italy-Tours-in-Nature

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.