- Italy Tours Home

- Italy Ethos

- Tours 2023

- Blog

- Contact Us

- Dolomites

- Top 10 Dolomites

- Veneto

- Dolomites Geology

- Dolomiti Bellunesi

- Cortina

- Cadore

- Belluno

- Cansiglio

- Carso

- Carnia

- Sauris

- Friuli

- Trentino

- Ethnographic Museums

- Monte Baldo

- South Tyrol

- Alta Pusteria

- Dobbiaco

- Emilia-Romagna

- Aosta Valley

- Cinque Terre

- Portofino

- Northern Apennines

- Southern Apennines

- Italian Botanical Gardens

- Padua Botanical Garden

- Orchids of Italy

Vajont:

a Space for Memory -- and a New Lease of Life after the Tragedy.

The valley of the Vajont lies on the western fringes of the Dolomiti Friulane Regional Park, in the region of Friuli but very close to the border with Veneto. Probably, this would be quite an unassuming place, if an event occurred in the early 60s – turned eventually into a disaster – had not made this little corner of the Alps known nationwide and beyond.

Nowadays, nearly 40 years down the line, the scars left by this tragedy are still visible on the land, but at the same time the valley – virtually abandoned after the event – has slowly come back to a new life, thanks also (and perhaps mainly) to the active presence of the park (see above a view of the Vajont valley, with the village of Casso in the foreground).

But to tell the story properly we have to go back to those early days – and this is how it goes.

The Story of the Vajont Valley

Between the 50s and the 60s, the Vajont stream was blocked by a dam a few hundred meters away from the confluence with the river Piave, and this dam was set to become the highest in the world. The hydroelectric plant that was built on that occasion was destined to be the hub of all energy production in the surrounding valleys.

This plant, though, was never officially used, because tragedy stuck first. The mountainside along the newly created basin was in fact unstable right from the start, and eventually a huge landslide fell, partially filling the artificial lake, and giving rise to a terrible wave.

It was on the night of 9th October 1963, and it all happened very quickly: in a matter of seconds, the isolated houses along the lake, the town of Longarone and other villages in the Piave valley were swept away; more than 2,000 people lost their lives. The local township of Erto was also badly damaged, and there were casualties, but at least the village had not been flattened to the ground.

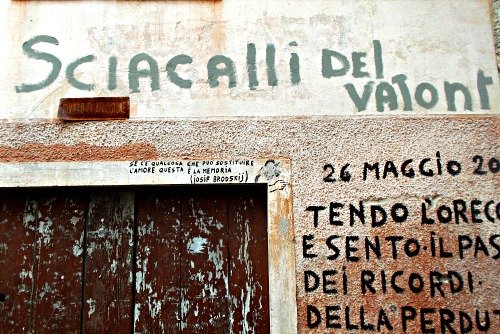

However, the landslide of the Vajont is only the most recent and dramatic event in the life of the valley, during which time the mountains were formed, lifted, and subjected to erosion. Indeed, everything began well before that dramatic night, when the building of the dam, with the consequent submersion of the valley floor, led to the loss of the few poor resources (mainly meagre pastures) of the people living there (in the picture below, see one of the murals still present along the streets of the village, denouncing the exploitation of the valley).

The construction of a dam in a valley that was deemed geologically unstable – and therefore unsuitable for such a massive entreprise – was one of the main causes for a landslide of such huge proportions (270 million cubic metres), which in that infamous night detached itself from Monte Toc (1,921 m) and rapidly fell into the partially filled lake.

The 265-meter high arch dam was in fact already, by then, the highest in the world, and was able to withstand the unprecedented destructive power of the landslide and the subsequent wave – in fact, so strong it was that the water was raised high in the sky and then precipitated with unimaginable force on the underlying Piave valley, gaining speed all the while.

The following morning, where once stood a thriving town of 4,000 – Longarone – a desolate, wide expanse of gravel and mudflat was all that remained. It must have looked like a Doomsday scene: half of the population had been decimated by the killer wave.

After that came the long, painful history of recovery, for which there is ample documentation (see for example the exhibits at both Longarone and Erto); for the purposes of this writing, though, suffice it to say that the big turning point came around and after 1996.

At that stage, some of the old inhabitants of the abandoned village of Erto had already started to make a timid comeback, when the area suddenly received a boost with the creation of the Dolomiti Friulane Regional Park (below, an image of the old houses of Erto).

Truth to be told, in the meantime theatre director Marco Paolini (a very well-known name in Italy) had refreshed the memory of the Italians – all too prone to forget – with a moving open-air performance on the dam itself, thus remembering a tragedy that by now had nearly been forgotten, and for which justice – on a sheer judicial level, and in terms of responsibilities – had never been properly passed.

Thus the Vajont valley, with the villages of Erto and Casso, slowly but steadily entered a new phase of its history – and life gradually came back again.

The Villages of Erto and Casso

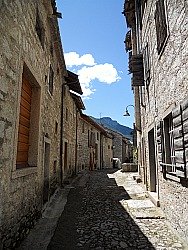

Situated on very steep slopes, the two communities still bear the marks of the disaster, but life has made a return in between the narrow alleyways that are flanked by old, tall stone houses in typical Pre-alpine style. Artisan workshops of woodcarving and a couple of cosy inns have opened up – overall, the impression is that of rustic authenticity (below, a picture of the historical part of Erto).

During the summer months, the dam – which is still standing intact – is open for educational purposes, and it is possible to take a guided visit on the edge of it: although party filled by landslide debris, and with hardly any water left in it, what was once the artificial lake is still an impressive sight – even more so when looking down on the other side, from where it is easy to imagine the narrow Vajont gorge acting like a funnel that precipitated the water straight over the clearly visible – and now reconstructed – town of Longarone, in the underlying Piave valley.

After that, in the Erto Visitor Centre, one can see the exhibit “La Catastrofe del Vajont, uno spazio della memoria” (“The Vajont disaster, a space for memory”), displaying a detailed documentation that describes the tragedy in all of its stages. Near the dam there is an an information point with seasonal opening, where you can also get the ticket for visiting the dam – should you wish to do so.

Erto is also the hometown of mountaineer, woodcarver and now writer Mauro Corona – a character in his own right, very well-known locally but by now also nationwide: with a red bandana on his head and a white vest that make him look like an unusual “mountain pirat”, you can’t mistake him if you see him around the village. It would be a rare honour to enter his workshop: a den where woods of all sorts fill in the dark space with their scents and different character – but perhaps it is more likely to spot him in the local osteria (even though he claims he's given up drinking...). In some ways, after the tragedy, Erto has come back to a second life, and even though life has been returning slowly, the arrival of the Albergo Diffuso and other initiatives means that many of the old stone houses have been carefully restored and could come back to their former glory (see image below).

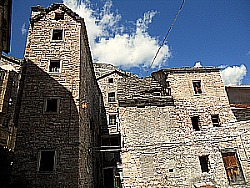

Casso, on the contrary, lies high above the dam, and so escaped the disaster altogether, but the overall economic conditions of the valley were such that most of the people emigrated anyway. Now, here as well life has made a timid but clearly detectable comeback; especially so in the summer months, when walkers hiking in the surrounding peaks of the so-called Dolomiti d’Oltrepiave – that display interesting geological phenomena – contribute to animate the place (in the picture below, Casso’s fascinating cluster of old stone houses).

From Casso it is also visible in all of its dramatic effect the infamous “M-shaped” scar on the flank of Monte Toc (1,921 m): this is the mark left by the massive chunk of rock that detached itself from the mountain and slid into the Vajont lake nearly 40 years ago – so you can gain for yourself a tangible idea of its sheer size (in the image below, a partial view of the dam; notice also the “M-shaped” scar on the mountain side).

So when you come here, take your time: pause for a while, look around, and listen to the wind rustling through the trees: it is a peaceful scene now, but ponder how the forces of nature – coupled with the arrogance and greed of man – could change the destiny of an otherwise quiet Alpine valley forever.

Places of Natural Interest Around the Vajont Valley

The Moliesa rock-climbing site

The cliff where training for rock-climbers takes place is in the vicinity of the infamous Vajont dam and lake, roughly half-way between the two villages of Erto and Casso. This site was created in 1978, and it has quickly become one of the most famous and renowned spots in the world to train for this activity (as well as being a geologically relevant site too).

Under the so-called Moliesa cliff there are around 300 climbing ways of all difficulties; in the central section – recognizable by the typical yellow-ochre color – are the most difficult ones, with routes reaching the 11th degree (the most difficult). Anyway, there is ample choice here, and each climber will find the way suitable to them – there is even a route for children!

The “Libri di San Daniele” (St. Daniel’s Books)

These legendary rock formations are found near the summit of Monte Borgà, and heaps of rock layers will look to the observer precisely like open books put to lay on the ground on top of each other. These are the residue of rocks accumulated by the dislocation of a fault-line on Monte Borgà (2,228 m), and are constituted of a very resilient type of rock. Despite the altitude, being the area nearly flat, this has allowed a good preservation of these most peculiar formations.

The “Trui dai S’ciarbon” (The Coal’s Trail)

This is a trail that connects the beginning of the Val Zemola to the hamlet of Casso. It is the track along which coal once used to be carried on one’s shoulders from the wood known as “the Val”.

This trail, restored by the Park authority, was used until the first few years of the 20th century to carry the coal from the Val woods and the Val Zemola to the Piave valley down below. Coal – created by the anaerobic combustion of wood – was trasported mainly by women, who would reach on foot the bigger deposits along the valley floor.

This easy trail, suitable to all abilities, allows the chance to reflect on the many aspects of this land – the traditional activities of the past, the delicate balance between man and nature in the wild and rugged environments of this valley – as well as offering a wide view over the imposing and infamous landslide on the other side, for which the valley sadly became known.

The trail begins in the vicinity of Erto, from which one follows the indications to the Val Zemola, until reaching the starting point of the path, branching off to the left by a bend of the road (a board indicates it). The track is clearly visible; it is parallel to the valley floor and the main road down below, as it proceeds almost horizontally to reach eventually the hamlet of Casso, while crossing patches of woodland alternated with rock and scree.

In fact, the position of this trail allows the walker to gain a gradual, complete view over the whole lenght of the landslide that detached itself from Monte Toc (1,921 m) on the night of October 9, 1963: this shows how extensive the earth and rock movement was (the front of the landslide is over two kilometres long, in fact).

Once crossed a huge scree, the trail climbs up a slope by some old rural stone buildings that were initially abandoned after the disaster, then it lightly descends to cross a section covered by huge rock boulders: these are the remains of yet another historical landslip, which precipitated in the 17th century, and the rocks have established themselves since then. Once crossed this old landslide, one quickly reaches the trail's final destination – Casso.

The Old Legend of San Martino

Let us now close with a local legend. The old people in Erto still tell this story: Once upon a time there was castle in San Martino, but now only a hill remains with that name, and you can still take drinking water from the “Górc dal Castél”, or castle fountain. A long stairway leading all the way up started from the chapel that was washed away on October 9, 1963, the night of the catastrophe. It is believed that this chapel was originally built on the ruins of an old Pagan temple. In front of the castle and beyond the lake, the “àndhre de la Regina” – the Queen's cave – remains with the “s’ciara”, the mooring ring for her boat.

Return from Vajont to Dolomiti Friulane

Return from Vajont to Italy-Tours-in-Nature

Copyright © 2012 Italy-Tours-in-Nature

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.