- Italy Tours Home

- Italy Ethos

- Tours 2023

- Blog

- Contact Us

- Dolomites

- Top 10 Dolomites

- Veneto

- Dolomites Geology

- Dolomiti Bellunesi

- Cortina

- Cadore

- Belluno

- Cansiglio

- Carso

- Carnia

- Sauris

- Friuli

- Trentino

- Ethnographic Museums

- Monte Baldo

- South Tyrol

- Alta Pusteria

- Dobbiaco

- Emilia-Romagna

- Aosta Valley

- Cinque Terre

- Portofino

- Northern Apennines

- Southern Apennines

- Italian Botanical Gardens

- Padua Botanical Garden

- Orchids of Italy

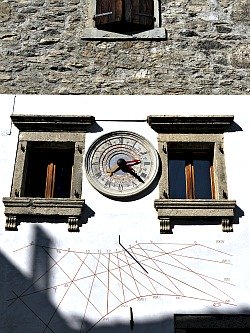

Pesariis, Secluded “Village of the Clocks” in the

Dolomites of Friuli.

Pesariis is famous for a feature for which it could well be

called the “Village of the clocks” (see an image of the main square above).

Millions of people around the world cast their eyes daily on tower, railway and town hall clocks that are likely to come from this little village, tucked away in a remote corner of the Eastern Dolomites (Dolomiti Friulane).

More specifically, the clocks are manufactured by the local factory of the Fratelli Solari, based in Prato Carnico – the municipality to which Pesariis belongs.

In fact, the name of the locality derives from the presence of a custom house with a weigh-house ('pesa' in Italian), which used to control the commercial traffic between Carnia and Comelico through this valley.

This village was already an important artisan centre in the 17th century, and the blacksmiths’ art – which was quite widespread and held in high account – was to constitute the fundamental basis on to which the technical knowledge needed for the production of tools of precision such as clocks would be based.

Initially, the first clocks – especially “grandfather clocks” – were realized on demand, to satisfy the requests of local noble families. But in 1725 the activity of the Solari firm was officially established, and the ‘farie’ – as the workshop would have been called in Friulano, the language of Friuli – was in Pesariis, where the tools of this ancient workshop could harness the water power from the local stream, as it tumbled down the mountain.

Gradually, in the second half of the 18th century, the production of clocks took off, and became eventually the absolute privilege of the Solari family, who imposed themselves on the market thanks to their entrepreneurial abilities.

At that time, every single individual part of the mechanisms of a clock would have been fashioned manually, working iron with the cold method.

Today, the “Museo dell’Orologeria Pesarina” is one of the few realities of this kind in Italy, and the clocks which are conserved in the museum have considerable importance also for the valorization of local culture.

That is the reason why the municipality of Prato Carnico, in these last few years, has tried to collect the maximum number of documents and finds, on the premise that this heritage constitutes the fundamental basis for a deeper understanding of the evolution of technological knowledge in the area.

At the moment, there are about 100 specimens of clocks of various epochs and provenance in the museum: its permanent collection offers a vision on the production of clocks that begins with rare examples dating to the 17th century, and ends with the modern indicator-clocks that offer a wide range of information other than time (in the picture above, another image of Pesariis, the “Village of the clocks”: the ancient sundial on Casa Cappellari).

The “Route of Monumental Watch-making” can be defined as an open-air museum that integrates and completes the actual exhibition with an itinerary centered around monumental clocks which have been carefully studied and designed to represent in various art forms the passing and measurement of time.

Up to now, 14 out of the 23 monumental clocks that have been planned for this project have been realized: the first one welcomes visitors at the entrance of the Val Pesarina; 12 of them have then already been installed along the streets and alleyways of Pesariis itself, while another one has been positioned at the entrance of the town hall (in the image above the starting point of the “Route of Monumental Watch-making” in Pesariis).

Among those that are located along the route in the centre of Pesariis, one can admire:

– the “Orologio a palette giganti”, which is composed of a series of revolving propellers that open like a book;

– the “Orologio a vasche d’acqua”, which can be referred to the type of the water hourglass;

– the ‘Meridiana’ (sundial) on Casa Cappellari, dating 1770, which is the only solar quadrant existing in the village, and displays two different ways of counting time, according to Italic and German hours (this is pictured further up the page);

– The “Orologio a scacchiera” offers a direct reading, while in the “Casa dell’Orologio” (the ‘Clock House’) the quadrant dates back to the 18th century, and has been restored with its missing parts; the mechanism of the hour hands is that of a traditional tower clock.

– In the “Orologio ad acqua a vasi basculanti” time is indicated by the alternate filling and emptying of two vases that united form the platform scales (‘bascule’).

– In the horizontal (analemnatic) sundial the shadow line is being replaced by the actual viewer, thus turning him or her into a ‘living sundial’.

– The “planetary clock” represents the solar system in the real version of Copernicus and Galileo, which differentiates it from the old clocks that would have put the earth at the centre of the universe.

– The “Orologio planisfero” illustrates the stars that are in the sky at any given moment of the day, while the ‘carillon clock’ uses bells that can perform musical tunes and even reproduce complete music pieces (see image below).

– The “Orologio ad acqua a turbine” can be referred to an experimentation that dates to the period between the end of the 16th century and the middle part of the 17th century, when exploitation of water power to activate clocks was tried.

– The “Giant Perpetual Calendar” refers to the more complex quadrants of tower clocks that used to contain other important pieces of information of public utility such as the date; they were sort of calendars at the service of the community, which would give indications also on the evolution of main astrological phenomena (which once were quite important for agricultural works).

– The “Orologio con automa” is the latest edition in a generation of mechanical tower clocks with electrical winding-up systems, and it strikes the hours on a bell with the aid of an automaton.

– Lastly, the “Orologio con eclittica” indicates the course of the Sun as seen from the Earth, through the various constellations of the zodiac.

Casa Bruseschi

Another interesting place to visit in Pesariis is the Casa Bruseschi (see image above), which has been – from the 17th century onwards – the residence of the Bruseschi, one of the most ancient and important families of this characteristic village (their origins date as far back as the 15th century).

At first, this precious heritage building, for the evidence it contains – extraordinary both from an architectonic and ethnographic point of view – had become property of the local parish, and was originally opened to the public as a “Museum of the Carnian Home”, only to become at a later stage part of the Carnia Musei network.

The house – of the terraced type – is arranged on three floors; its furnishings evoke the human drama and the customs of a typical Val Pesarina family, allowing visitors to comprehend how life was organized on a daily basis in the region of Carnia, in a wealthy environment but within a context nonetheless strictly connected to the agricultural world.

Once into the building, one first enters the dinette – the room that was destined to welcome guests. On the right of the corridor, a window gives directly onto the kitchen: this room was traditionally the centre of family life, and its fogolàr (‘focolare’ in Italian – the hearth), disposed against the external wall of the house, has the peculiarity of not being equipped with the typical hood for the smoke, which could escape only out of a small window to the side, using the natural draft. When this system was not working, though, the room would fill with smoke – and this is the reason why the kitchen was isolated from the rest of the house by a glass door.

A relevant item to be admired here is the ‘panaria’ (bread cupboard), dating to the 15th century: this historic piece of furniture used to contain both the bread that was produced in the house and the tools needed to make it. In the kitchen there is also a stone sink, over which hangs a wooden plate rack.

Always at the ground floor is the dining room, with a central table, nice sitting stools and the big cupboard, overarched by a big vaulted ceiling – a clear indication of the fact that the house once belonged to a wealthy family.

The stairs that lead to the first floor are embellished by meaningful representations of sacred iconography – prints on the life of Saint Benedict, indicating that the Bruseschi were quite a devout family (in fact, they counted many religious figures and priests among their ranks). Along the corridors are also interesting bridal chests and a wardrobe dated 1741.

On the first floor are the studio and the bedrooms. The studio is a working space linked with the profession of lawyer, exercised by a member of the family around the second half of the 18th century. The mirror – in all likelihood of Venetian make – the sofa and the twelve chairs were acquired only at a later stage.

The last inhabitants of Casa Bruseschi had turned the studio into a living room – a space of memory where the portraits of the ancestors would be displayed, and where they can still be seen today. Close to the studio is also a bedroom that contains the original bed, the rounded cabinets, the nightstands and a kneeler.

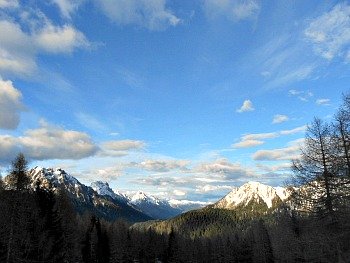

The Val Pesarina and the Dolomiti Pesarine

The Val Pesarina – also known as Canale di San Canciano – is one of the seven valleys of Carnia, and it develops in a west to east direction for about 20 km (see a panoramic view of the valley in the picture above).

It is crossed by the Pesarina stream, from which it derives its name, and it is a relatively narrow valley, dominated to the north by the Dolomite peaks of Monte Pleros (2,314 m), Siera (2,448 m), Creton di Clap Grande (2,487 m) and Clap Piccolo (2,463 m), which contrast with the more rounded and softer shapes of Monte Forchia (1,901 m), Pieltinis (2,027 m) and Novarza (2,024 m) to the south.

Of course, the Val Pesarina allows for many excursions in nature. The area of Casera Razzo (by the Sella di Razzo, 1,760 m) can easily be reached from Pesariis, and from there one can connect with the Lumiei valley and Sauris (several roundtrips are possible; more on this below), as well as with nearby Cadore through the Sella Ciampigotto (1,790 m), from where one can directly reach Vigo di Cadore (bearing in mind that in winter, when the connecting roads are closed for heavy snow, neither of these possibilities are viable).

Many interesting and mostly solitary walks can be taken on the open plateau of Casera Razzo itself during the summer months, with further possibilities to reach the Comelico area and Sappada through the Forcella Lavardet (1,542 m) and the val Frison.

The so-called Dolomiti Pesarine, which are disposed in a coronet above the valley head, can be considered a part of the Dolomiti Friulane and d’Oltrepiave, and among the least frequented Dolomites; they generally allow for walks in a setting which is far less crowded than the Dolomites’ heartland, while at the same time lacking nothing of the natural beauty which is traditionally associated with these majestic mountains.

Geographically speaking, the Dolomiti Pesarine are also part of the wider Alpi Carniche chain (Carnian Alps), and are divided into three sub-groups. They count among their peaks – in addition to those already mentioned above – Monte Creta Forata (2,462 m) in the Siera sub-group; Monte Cimon (2,442 m) and Cresta di Enghe (2,441 m) in the Clap sub-group and lastly Monte Terza Grande (2,586 m), Media (2,434 m) and Piccola (2,333 m) in the Terze sub-group.

The best base for excursions on these mountains is Rifugio De Gasperi (1,770 m). It is also possible to connect to the Via delle Malghe in Sauris, which can be reached via long but not difficult paths that first reach Casera Rioda, Casera Malins or Casera Vinadia Grande and then join the Via delle Malghe network past the watershed with the Lumiei valley (in the closing image below, a view of the small plateau over which the village of Pesariis lies; notice the interesting pattern of the ancient agricultural organization, with small patches of cultivated fields).

Return from Pesariis to Carnia

Return from Pesariis to Italy-Tours-in-Nature

Copyright © 2012 Italy-Tours-in-Nature

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.