- Italy Tours Home

- Italy Ethos

- Tours 2023

- Blog

- Contact Us

- Dolomites

- Top 10 Dolomites

- Veneto

- Dolomites Geology

- Dolomiti Bellunesi

- Cortina

- Cadore

- Belluno

- Cansiglio

- Carso

- Carnia

- Sauris

- Friuli

- Trentino

- Ethnographic Museums

- Monte Baldo

- South Tyrol

- Alta Pusteria

- Dobbiaco

- Emilia-Romagna

- Aosta Valley

- Cinque Terre

- Portofino

- Northern Apennines

- Southern Apennines

- Italian Botanical Gardens

- Padua Botanical Garden

- Orchids of Italy

The Peaks of the Vette Feltrine: Nature’s Living

Encyclopaedia.

The Vette

Feltrine form a majestic

backdrop to the historic town of Feltre – and most people, perhaps, do not venture

beyond that. Yet, they are an amazing set of mountains, wild and rugged, full

of motives of interest ranging from the botanical to the geological and the historical.

They are contained within the boundaries of the Dolomiti Bellunesi National Park, and protected by this extensive nature reserve that covers 32,000 ha (79,075 acres), running in an arc above the val Belluna between Feltre and the provincial capital of Belluno.

Displayed in a coronet above Feltre, the Vette Feltrine are gathered around the peak of Monte Pavione (2,334 m), and each massif is divided from the next by a series of deep valleys; in the Feltrino area, the main ones are the Valle di Lamén and the Val Canzoi.

The easiest way to access the Vette Feltrine is either through Passo di Croce d’Aune (1,011 m; about 10 km from Pedavena, north of Feltre) – or from the solitary Val Canzoi (see below), which can also be entered from the town of Cesiomaggiore, a short distance east of Feltre.

Pedavena and Passo Croce d’Aune

The town of Pedavena is perhaps best known for its brewery, founded in 1895, whose main product (“Birra Pedavena”) is still extensively available today in most local shops and bars, as well as in the historical brewery itself (frequented also for its restaurant).

But Pedavena is renowned for the magnificent Venetian villa Pasole-De Berton too, a notable building erected in the 17th-18th centuries with two side loggias and a grand staircase, which features also an Italianate garden with a fish pond (peschiera), old Venetian-style statues and clumps of hornbeams clipped in the traditional style (carpinete).

It is certainly the most impressive example of villa veneta in the whole Val Belluna. Its garden is officially private, but being open, you may just be lucky enough to briefly sneak into it.

Nearby is the “Sasso nello Stagno” (‘Stone in the Pond’) – the main visitor centre for the Dolomiti Bellunesi National Park, which can serve as a base to gather information and maps for visiting the vast area of relative wilderness concealed by those very Vette Feltrine that provide such a majestic backdrop to the skyline of Feltre.

As anticipated earlier, most paths to the Vette Feltrine can be taken either from Passo di Croce d’Aune (1,011 m) or the village of Aune itself – just above Pedavena. Alternatively, they can be accessed from the solitary Val Canzoi, which can be entered from the town of Cesiomaggiore (about 10 km to the east of Feltre).

Croce d’Aune pass is very close to Monte Avena (1,454 m), a rounded mountain which is also an important archaeological site; here remains were discovered of a lithic industry dating back 30,000 years ago, which makes this one of the most important sites where to witness the presence of man in altitude in the Alps in Pre-historic times.

From Passo di Croce d’Aune, situated at about 1,000 m of altitude, it is relatively easy to penetrate into the heartland of the Vette Feltrine’s wildest area, and one has the choice to either use the long and twisted military road that ascends to Rifugio Dal Piàz, or to cut through the mountainside using much shorter – but steeper – paths.

Rifugio Dal Piàz and the Busa delle Vette

The Rifugio Dal Piàz (1,993 m) is a conveniently located facility from which to venture into what may easily look like uncharted territory. In fact, it isn’t – as the National park maintains and properly marks a number of paths that zigzag the area in altitude, but one shouldn’t underestimate that these are ‘real’ mountains nonetheless, and therefore all the usual precautions needed when walking in harsh natural environments must be taken (checking weather conditions, appropriate clothing and footwear, a compass, water and emergency high-energy foods like nuts and chocolate).

The military road that ascends to the Dal Piàz mountain hut from Croce d’Aune is a feats of engineering about 11 km long, and it represents a valid, undervalued alternative to the path. For one, it is a much easier option to the steepness of the paths, as it allows a much gentler approach to this mountain, allowing to better appreaciate its riches (see below an image of the military road, with a series of hairpin bends that tackle the mountainside with a gentler gradient).

An incredible sequence of rock formations accompany the walker along the higher section of road, while rewarding blossoms will follow you all the way to Rifugio Dal Piàz during the flowering season. In spring, I have been delighted by endless displays of deep-blue trumpet gentians (see first image below), bright yellow Auricula primroses (second picture below), white Alpine buttercups and anemones, pink creeping Rhododendrons and purple orchids.

More unusual species that can be encountered along the way include Pedicularis and Pinguicula – a small carnivorous plant with either white or purple tiny blossoms – while in summer this is a feast for the many different types of Saxifrages nestled among the tormented rocky outcrops.

This is already amazing to the eye and all the senses, but in fact the real exceptionality of this place becomes evident only further on.

A Plantsmans’ Paradise

Just beyond Rifugio Dal Piàz an incredible area extends, much valued by geologists and botanists alike, and known as Busa delle Vette. In fact, not many people know that the Vette Feltrine, together with Monte Serva (near Belluno) are a paradise for their flora, and have been held in high esteem by many illustrious botanists since at least the 17th century. Places such as these were once known as ‘horti’ (from where we get the Italian term “Orto botanico” – something like a Physic Garden).

In fact, it is worth pointing out that the flora of the Vette Feltrine alone represents beyond one quarter of all the national flora of Italy; in a single quadrant of about 30 square metres are gathered something like 1130 species!

Of course, there are several concurring factors to explain such a plenty, and I will now mention some of them.

The most common types of vegetation in the Vette Feltrine are associated with the Alpine (particularly in the eastern sector), the Boreal and the Eurasiatic-temperate vegetation zones – and the key as to why the Vette Feltrine are so important for their flora lies precisely in their geographical location.

As outposts of the Alpine chain during the last glaciations (places known as Nunatakker), they offered refuge to many species that remained isolated there ever since – a destiny that these peaks share with other outlying ranges in the Southern Alps such as Monte Serva, Monte Faverghera and Monte Baldo.

But what is peculiar to the Vette Feltrine is that, on top of this, still today they act almost like a crossing point, where many species coming from different directions meet. Often at the margins of their natural area of distribution, those species find here their most outlying stations – which is primarily what makes the Vette Feltrine so outstanding and unique.

In simple terms, one could almost say that these mountains are located at the crossroads between several botanical migration routes, which – being plants not as mobile as animals – occurred over an incredible length of time.

Hence, we find here Arctic species – relics of a much colder climate, having descended from the north – while eastern species that are typical of the Illyrian and Carpathian mountains have established in the Vette Feltrine their westernmost outposts.

More recent introductions have risen from the much warmer Mediterranean climate to the south: all these different plants mingle here to create a unique “floral party” which gathers more than 1,500 species, and that has very few equals in the Alps.

The Vette Feltrine are also a so-called “locus classicus” for a few species (such as Thlaspi minimum, Minuartia graminifolia and Rhizobotrya alpina) which have been discovered in this area for the first time, and that were often named after the scientist responsible for their discovery.

Still to this day, plant-hunters flock to these mountains in late spring-early summer to admire some of the species which have been instrumental in the creation of the Dolomiti Bellunesi National Park.

Amongst them, most notable are Alyssum ovirense, which blossoms with cushions of tiny yellow flowers at the beginning of summer: thanks to a surprisingly extended network of roots, this Illyrian species forms widespread colonies covering with a yellow carpet what was snow-covered detritus in winter – in locations where it also gets very hot in summer.

The Alyssum can be found only on Monte Pavione, the Busa delle Vette and on Monte Serva. Delphinium dubium (a larkspur) is a plant belonging to the Buttercup family (Ranunculaceae), blooming in full summer in some screes of the Vette Feltrine; Thlaspi minimum (a small Cruciferae with white flowers that lives on detritus too) was discovered for the first time in 1763 in the eastern section of the Vette Feltrine, from Vallazza (2,167 m) to the Val Canzoi, where Iris cengialti and Hemerocallis lilio-asphodelus can also be admired.

Cortusa matthioli is a delicate-looking plant belonging to the Primrose family with beautiful purple-pink flowers; it is common in the western area of the Park, from the Vette Feltrine to the Valle del Mis; its ideal habitat is shady and cool places covered with snow for most of the year, rich in nourishing substances.

Lilium carniolicum is a wonderful lily growing only on grassy-rocky slopes with a south-facing aspect: this is yet another of those Illyrian plants living here at the westernmost edge of their usual distribution area.

Rhizobotrya alpina is also a protected rare endemic species of the Dolomites, living on wet gravel at high altitudes; this plant has ancient origins too, and it has been first recorded in the Vette Feltrine in 1833.

The Campanula morettiana, chosen as the park’s symbol, is an endemic species of the Dolomites that can be commonly found in the whole area of the Park, but especially so on damp cliffs above 1,000/1,200 metres, where it blooms in full summer. Its blooming frequently occurs together with another beautiful species, Primula tyrolensis.

Geological Aspects

But the area is notable also for its geological relevance: the western area of the Park – that of the highest summits of the Vette Feltrine – is characterized by peaks covered with grass (the most famous of which is perhaps the pyramid of Mt. Pavione, at 2.335 m) and by wide strata of detritus, glacial cirques and karstic basins – all remnants of the Quaternary glaciations.

Indeed, the military road that ascends to Rifugio Dal Piàz is often cut into very interesting formations, often structured in layers (as it can be appreciated in the picture above) that contain most of the rock types to be seen in the area, displaying different consistencies and colors.

And geology – with the associated variations in the subsoil composition – is another factor responsible for the incredible richness and variety of the flora, as the dominant rocks are of sedimentary origin (limestone, Dolomite), but there are also outcrops of crystalline rocks, as well as some sediments of volcanic origin.

The so-called Biancone – an ivory-white rock with frequent nodules or stripes of grey or black flint, characterized by a typical concoid fracture (as in glass) and a very thin grain – forms the three top pyramids of the Vette Feltrine, emerging from the steep slopes at the foot of Sass de Mura (2,547 m), on the southern slope of Mt. Grave and on Monte Tre Pietre (1,965 m).

The most recent geological formation within the Park is the Scaglia Rossa (Upper Cretaceous). This is a brick-red or grey-rosy marly limestone outcrop that can be found near Rifugio Boz (1,718 m), on Monte Brendol (2,150 m) and on Monte Tàlvena (2,542 m; the toponyms Le Rosse di Erera, Le Rosse di Vescovà and Val dei Ross all clearly take their name from the red color of this rock). The Scaglia Rossa originates from mudflats deposited in a deep-sea environment, but it contains a considerable quantity of clay, with many traces of fossils.

The eerie limestone wastes and glacial cirques of the so-called “Busa delle Vette” form a wide karstic plateau furrowed with sink-holes (doline) and other karstic formations, encircled by peaks also rich in fossils and with a complex geological story to tell.

Another aspect worth mentioning is that the Park authority has been responsible, over the last few years, for restoring a number of old sheep-pens and former dairies locally known as ‘malghe’.

These are long-standing memorials to the area’s pastoral tradition, and now – thanks to the Park intervention – some of them have been reinstated in their former, original destination as working dairies, while others have been turned into facilities well equipped with the most advanced solutions in terms of environmentally friendly technology, for the benefit of the stranded walker.

From Rifugio Dal Piàz and the “Busa delle Vette”, the possibilities to continue to walk in altitude are endless – and indeed, the trails are some of the quietest in the region. The area is also crossed by the Alpine Highway no. 2, known as ‘of the Legends’ (“Alta Via n.2, delle Leggende”), which connects Bressanone/Brixen (in South Tyrol) to Feltre across a section of the Dolomiti Bellunesi National Park.

Every summer, parties of dedicated trekkers spend days – if not weeks – in the vast solitude of this upland region, rambling from hut to hut: most of the mountain huts offer organized accommodation – sometimes very basic, but in other cases you will be amazed at the level of comfort offered.

In some instances – such as for the pens described above – one is allowed to use these facilities to spend the night free of charge, but they have to be seen as fortune shelters, and one must therefore have one’s own sleeping equipment, expect to possibly share the space with others, and be prepared for a rougher accommodation than in a proper Rifugio.

The border with Trentino to the north allows an easy straddle into this other most magnificent part of the Dolomites, while continuing further east – but remaining within the boundaries of the park – one encounters an endless sequence of rocky and uninhabited peaks that gradually lead into the heartland of the Dolomiti Bellunesi National park.

The Val Canzoi and the “Covoli di Lamén”

As said before, the easternmost section of the Vette Feltrine can also be accessed from the solitary Val Canzoi, which starts as a narrow canyon just north of Cesiomaggiore (about 10 km east of Feltre).

After an initial narrow gorge, this valley is occupied in its lower reaches by a vast, artificial basin (the Lago della Stua), past which paths start climbing in altitude towards Monte Pizzocco (2,176 m), at whose base are the cave-riddled Piani Eterni – the ‘eternal plains’ – where Dolomites and Pre-alpine features meet and mingle perfectly.

Back towards Feltre, past Pedavena one can also access the solitary Valle di Lamen, which takes its name from the tiny village at its entrance (see an image of the valley entrance below).

This enclosed valley leads you into an area which is very important for its archaeological finds – and for that reason, the park has created here a circular trail themed around the so-called “Covoli di Lamen” (more on this below).

These are wide natural caves that were intended originally as shelter by Pre-historic populations, but were – many centuries later – also used by herdsmen who would take their flocks in altitude for summer grazing, thus demonstrating an incredible continuity of use in what seems to us today a totally inhospitable environment.

This circular trail is quite long; some sections of it are very steep, and the markings are not always clear; therefore, it must not be undertaken lightly or with forecasts of inclement weather.

The Valle di Lamen (Lamen valley)

The Valle di Lamen is a flat valley in its initial section. The Piave-Cordevole glacier formed here a typical escarpment, with a craggy morphology in active evolution that cuts with a steep valley head the southern edge of the Vette Feltrine in correspondence with the anti-clinal Coppolo-Pelf fault, in which the horizontal layers of the Vette Feltrine are folded at 90 degrees and create a typical ‘knee’ shape (above, an image of the curtain of mountains that enclose the Lamen valley head).

The Valle di Lamen is deeply cut into the solid banks of Main Dolomite and Grey limestone; to its moulding concurred ancient water courses and glaciers, which with their characteristic erosion and accumulation shapes have left a clear trace of their passing. The glacial morphogenetic action is recognizable also by the soft U-shape of the valley, and the widespread moraine deposits of the Piave-Cordevole glacier in the form of porphyry blocks, Phyllites, andesitic rock and green stone.

The most interesting morphologic peculiarity of the valley, however, is connected to the glaciations. In the phases of its maximum expansion, the Piave-Cordevole glacier penetrated deep into the Lamen valley, already excavated previously by other water courses. The glacier, which reached almost 1,100 metres of altitude, would discharge in the valley huge quantities of rubble from its right hand side moraine.

In the retiring phases, the thickness of the ice sheet would decrease to about 400-500 metres and the ice could not insert itself in the valley anymore, but its presence at the valley outlet constituted like a natural ‘dam’ that prevented the regular deflux of the stream’s water, and forced the Colmeda stream to discharge its detritus against the glacier.

This process led to the formation of the Lamen valley plain – a vast fluvio-glacial terrace recognizable on both sides of the valley, interrupted only by the furrow through which the Colmeda has cut through its own sediment (see the second picture above). On the steep slopes generated by the stream's erosion through the fluvio-glacial deposits the meteoric waters were washed away, and the superficial streaming has then originated some ‘calanchi’ shapes, earth pyramids and a multitude of small, minor landslides.

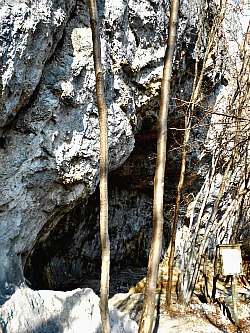

Another characteristic of the Valle di Lamen is the diffusion of under-rock shelters, inhabited on several occasions from Neolithic times onwards up to the Middle age. To the development of these peculiar creations (known as ‘covoli’; see an image below) various phenomena have contributed: karstic corrosion, successive cycles of freezing/thawing, rock degradation – all processes that have operated with more efficiency in those bands of rocks which are more porous and sensitive to the action of ice, and for this reason also more easily erodible.

The diffusion in this area of these unusual and noteworthy rock shelters is to be put in relation with the Dolomite-limestone composition of the rocks, as well as with the relatively wet climate and the intense tectonic activity that has reduced the mechanic resistance of the rock, thus facilitating the coming off of rock boulders and thinner scales.

In the Valle di Lamen there is also an archaeological themed walk, which can be a lovely – and ‘positively lonely’ – experience. It can be organized in a circular fashion, but the whole roundtrip is quite long (and deceptively short if you look at the signs at the beginning, which make it look quite simple).

From the parking by a bend of the road near the valley head (where the tarred section finishes and there are some picnic tables), you have the choice of breaking the path into two sections and choose between two circular loops of different lengths, which make it a lot more manageable solution, as each of the sections is shorter than the whole circular trail.

From this point, if you take to the left, you can climb first to the “Covolo basso” (‘Lower shelter’), and break the path into a shorter roundtrip by descending along a stream bed just after passing the “Riparo Tomas” (‘Tomas shelter’; see image above), thus reaching the parking at the bottom (this option takes about 2 hours). Having the time, though, there is also the possibility of carrying on from there and do the complete roundtrip.

However, if you climb straight up from the parking along the stream bed instead, when you reach “Riparo Tomas” you can then take left for the longer roundtrip half; at that point the path becomes steep, as it climbs the slope with hairpin bends (it is the toughest section of the whole walk), taking you eventually to the “Covoli alti” (‘Upper shelters’), with ever wider views on the impressive rock faces and the craggy mountains at the head of the Lamen valley (see, below, an image of the typical rock faces that are encountered along the walk, where many of the covoli were also dug).

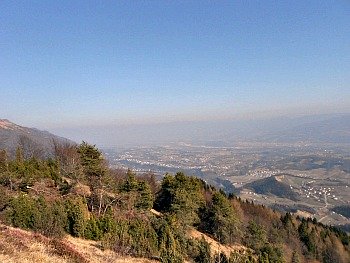

Continuing further still, the path will take you to the highest point of the whole walk – that is, the summit of Monte Pafagai: although not an impressive height in itself (about 1,100 metres), this summit allows for pleasant sights on the craggy tops of the distant Dolomites on one side, while on the other side the view opens up on the val Belluna below, with its many towns, villages and the hills behind them (see below an image of the view from the summit of Monte Pafagai).

The descent then takes you down to the Lamen valley floor again, dotted with old stone sheep-pens (see image below); once there, if you turn right the road will lead you back to the parking with a short walk. This section of round-trip takes 3 to 4 hours to complete, so if you decide to do the whole trail consider around 6 hours. This explanation may seem a bit complicated, but it will all make sense once there, or if you read it alongside a map.

Apart from the evident archaeological interest of the trail, this is still a relatively wild and quite untamed area, where it is not difficult to spot animals, such as chamois climbing up the narrow ledges. I still remember a close chance encounter with such animals on a solitary winter walk, which gave me the heartbeat: the emotion that came with it will not be easily forgotten.

The trail is marked with purple-yellow bands (the Park’s colours), although you will have to be on the constant lookout for these, as the signs are not always obvious or clearly visible. More information on the Valle di Lamen and the archaeological themed walk can also be found in the dedicated page.

The Valle di San Martino (St. Martin’s valley)

The Valle di San Martino is a variegated valley, presenting a diverse variety of geo-morphologic situations and environments. It is an open valley (although less so than the Valle di Lamen), almost parallel to the latter, but pleasantly secluded at the same time.

The St. Martin’s valley presents – taken in its entirety – a wide variety of geo-morphologic situations: several factors have contributed to its moulding, such as glaciers and water courses (it is in fact a fluvio-glacial valley).

The valleys that come down from the Vette Feltrine and that originate, at their confluence, the Valle di S. Martino proper are in fact typical ‘scarp valleys’ that cut the southern slopes of the Vette Feltrine. In the valley's transversal profile it is still possible to observe the markings left by glacial moulding, and one of the elements that best denote the valley floor is the relative abundance of water: small rivulets that are often fed by karstic wells and springs.

The most common type of rock is Main Dolomite: a powerful succession of fine-grained Dolomite of saccaroid aspect, white-coloured and easily fractured, that turns grey when it is altered by atmospheric agents – besides the zones where massive non-stratified nuclei of Dolomite appear.

Around the deep and most ancient ‘core’ of Main Dolomite there is a crown of Grey Limestone from the Lower Jurassic, which appears in the medium-elevated sections of the Vette Feltrine and at Monte San Mauro (1,200 m).

The valley develops on the southern flank of the Vette Feltrine, and attacks in profundity the Coppolo-Pelf anti-clinal fault-line, but the narrow visual, the lithologic uniformity of the valley bottom and the complications due to faults and over-thrusts do not allow to follow the development of the rock layers easily (see below an image of the rock formations in the lower valley floor).

A peculiarity is also connected to tectonics, and it is constituted by a small valley – the Val Pazzonega – which, differently from the other tributaries, enters the Colmeda stream against the flow: this is an anomaly of tectonic origin.

The St. Martin’s valley is structured in correspondence of a band of cataclastics produced along the Facen fault-line (which takes its name from a nearby hamlet). Additional confirmation of the presence of this fault-line comes from a small fault-table that can be identified on the dark vertical rock wall visible on the right bank of the Colmeda, a little upstream from the confluence with the Val Pazzonega.

The Valle di S. Martino can be easily visited from the village of Vignui; from there (where it is advised to leave the car if you’re driving) one soon enters the narrow gorge where the stream will be running alongside you. As the valley gets narrower and wilder, you will eventually reach the end of the road, which is the starting point for several paths that enter into the mountains and venture in altitude.

If you're not planning to walk on higher ground, the shortest option is to do a small roundtrip from there, just to complete the excursion; best is then to take left straight away, and at first keep following the water course.

Small deviations to the right of the path will allow you to give a look at the small – but very scenic – evorsion pot-holes (see picture below) formed by the Colmeda stream, where tiny flowers of Soldanella minima blossom in early spring. This geologic phenomena is very similar to the one that can be admired in the valle del Mis (the more famous Cadini del Brenton), but the difference here is that you will have the place more to yourself, as this valley is much less frequented.

At a junction by some old dilapidated malghe (dairy-pens) you can branch off to the right straight away, otherwise keep going until you reach Pian dei Violini and turn right there. You will then cross a section of old Norway spruce plantation that will take you to another junction with a marked CAI (Italian Alpine Club) path; take right again and you will close the circle.

Another interesting walk that can be done in the area is from the hamlet of Arson; this will take you to the little church of San Mauro (see picture below), along the themed path of “The Abandoned Churches” (Sentiero delle Chiesette Abbandonate), devised by the Park. It is quite a steep ascent, but it will reap its rewards as the trail crosses a still relatively wild area where it is not unusual to spot chamois and ibex.

The small church of S. Mauro lies in an incredibly solitary and most unusual location at about 1,200 m of altitude, and once there you will wonder how they managed to erect a building in such a spot – it seems like it could take a leap any moment! It certainly provides an interesting insight on the incredible faith of Medieval people, and their close connections with the imagery linked to the life of saints.

The return can be done via a path that crosses a patch of beech woodland and then opens up on to ancient meadows and pastures, from where you will enjoy wide views over the Valbelluna (see an image below). By a malga (dairy-pen) you will have to bear right, if you want to close the circle and go back to the beginning of the trail in Arson; if you keep going straight you will reach Cesiomaggiore instead.

The Vette Feltrine: Wild Nature for Everybody

All in all, one could say that the Vette Feltrine are one of the indisputable highlights of the Dolomiti Bellunesi National Park, for several reasons.

If the incredible richness of the flora is undoubtedly the prime motive of interest, the articulated orography, the complex geological history (readable in the marks left on the landscape by the glaciations and in the display of different types of rocks), the archaeological finds and the many other traces of human activity through the centuries all concur to create a unique environment which will satisfy you on so many levels, while always guaranteeing a full immersion in pristine nature.

Return from Vette Feltrine to Dolomiti Bellunesi

Return from Vette Feltrine to Italy-Tours-in-Nature

Copyright © 2013 Italy-Tours-in-Nature

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.